Astrophysicist’s Claim of Discovery of Alien Technology May Be Incorrect

Theoretical physicist Avi Loeb gained attention recently when he suggested that small spherules found in the ocean may have originated from aliens. In an interview with The New York Times, Loeb described them as a potential technological device with artificial intelligence. The newspaper has now published an article discussing the controversial nature of his claims. While bold hypotheses often lead to significant scientific advancements, many of Loeb’s colleagues do not consider his assertions to be based on sound scientific principles.

Loeb’s declarations stem from an object registered by US government sensors on January 8, 2014: a fireball from space that flared up in the western Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of Papua New Guinea. Highlighting its recorded speed and direction as anomalous, Loeb and undergraduate assistant Amir Siraj target an otherwise insignificant planetary entry as an object worthy of further study.

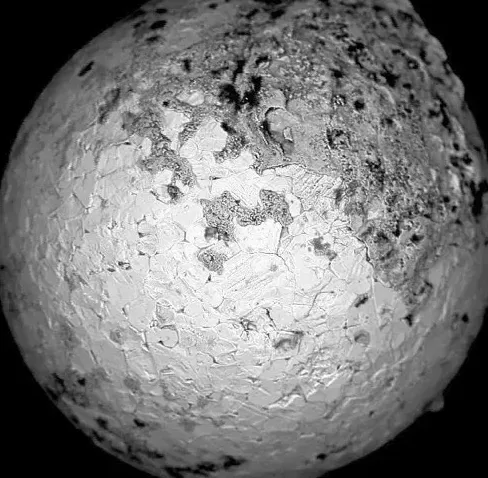

Flash forward to last month, when Loeb led a crypto-entrepreneur-funded expedition to collect evidence of the fireball’s calculated collision course. Dragging a magnetic sled attached to an excursion boat across the sea floor, the team found a number of small spherical objects that, according to Loeb, “look like beautiful metallic marbles under the microscope.” Preliminary analysis showed that the submillimeter spheres were 84 percent iron, with the rest silicon, magnesium and trace elements. Loeb believes that “as a result of exposure to the heat of the fireball, the surface of the object probably disintegrated into small spheres, the number of which per unit area is similar to the spheres recovered by the expedition”.

Loeb wrote in a Medium post that he is not very careful about public statements: “Their discovery opens a new frontier for astronomy, where what is outside the solar system is studied with a microscope and not a telescope.” He summed it up just as dramatically: “Finding the spheres felt like a miracle.” Shortly thereafter, CBS News picked up on his enthusiasm and published an attention-grabbing article titled “Harvard Professor Avi Loeb Believes He Found Fragments of Space Technology.” Loeb has sent the mystical orbs to Harvard University, the University of California, Berkeley and the Bruker Corporation in Germany for further analysis.

“The strength of that material is harder than any space rock previously seen and cataloged by NASA,” CBS News reported Loeb as saying earlier this month. “We measured its speed outside the solar system. It was 60 km per second, faster than 95% of all stars in the vicinity of the Sun. The fact that it was made of materials even harder than iron meteorites and moving faster than 95% of all stars in the vicinity of the Sun suggests that it could be a spacecraft of another civilization or some technological device.

It all sounds fascinating, especially given the resurgence of interest in UFOs and the quest to find signs of alien life. But there’s one problem: the scientific community at large believes that Loeb is, if not outright full of it, practicing something far removed from what they call science.

Peter Brown, a meteor physicist at Western University in Ontario, said that “several percent” of observed events appear to be interstellar at first, but almost always end up being a measurement error. Steve Desch, an astrophysicist at Arizona State University, argued at a recent conference that if the object had moved as fast as the data suggests — one of the points Loeb uses to show that it originated outside our solar system — it would have burned up completely in Earth’s atmosphere. Brown and other researchers also highlight Loeb’s lack of engagement with his peers who are investigating similar unidentified fireballs.

Brown recently presented data (accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal) showing that NASA’s records in such cases often prove unreliable. He believes the fireball likely crashed more slowly than the recorded data suggested. “If the velocity was overestimated, the object will more or less fall within what we see in other bound solar system objects,” he said. (Loeb responded by invoking an inept reliance on government data: “They’re in charge of national security. I think they know what they’re doing.”) The New York Times adds that the government is unlikely to declassify the data so the scientific community can learn how accurate (or not) it is.

Regardless of the origin of the spheres, researchers are concerned about Loeb’s willingness to venture outside of science to make bold (and very public) claims — his scientific background bolsters their perceived legitimacy. The crux of their alarm is that an astrophysicist at Harvard doesn’t give you a wizard-like ability to know the answers to questions that haven’t yet been confirmed by the scientific method. On the contrary, it is supposed to mean that your peers respect you with restraint and vice versa. “[Loeb’s claims are] a real breakdown of the peer review process and the scientific method,” Desch told The New York Times. “And it’s so depressing and tiring.”

Loeb’s views on the harsh reactions of his peers can be summed up in a quote he quoted from philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer in a recent blog post. “All truth goes through three stages: First, it is mocked; secondly, it is fiercely opposed; and third, it’s accepted as self-evident.” Loeb seemingly refers to his team’s preliminary findings—with numerous question marks still intact—as “the truth.”

The Oxford English Dictionary defines confirmation bias as “the tendency to interpret new evidence as confirmation of existing beliefs or theories.” Loeb’s words and excited tone suggest that he knows the answer, and that the criticism of his peers stems from their opposition to the new frontier he has discovered. However, their criticism is only partly affected by his specific conclusions; it comes with a greater concern about a respected cohort jumping to conclusions that fall far outside the scientific method. “What the public sees in Loeb is not how science works,” noted Desch. “And they shouldn’t go away thinking about it.”